Sharks! Course Review: Not all Sharks Have Huge Teeth

A well-rounded course that mentions just about any aspect of sharks that you can think of. Ecology, anatomy, behavior, interaction with humans, plus more.

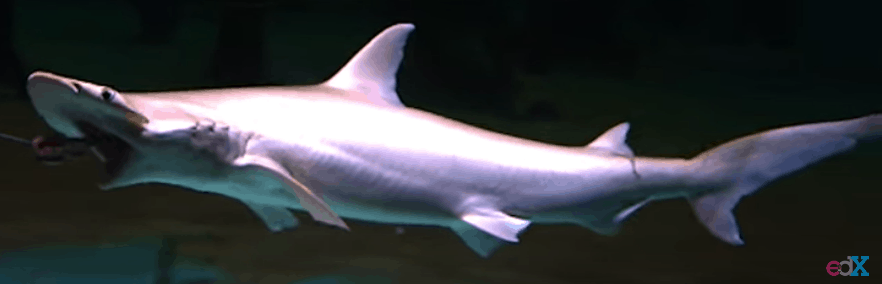

As a child, I often went to the coast with my family and have memories of occasionally being called out of the water because of a shark sighting. One day, the surf lifesavers (volunteer coast guard) caught a huge hammerhead shark and placed it on display for about a week before the fascinating but stinking carcass was towed back out to sea.

Such was life in the 1960s, before many shark species were listed as threatened or endangered. Sharks were seen as monsters, to be destroyed on sight. Yet, even as a child, I was fascinated by the variety of shapes and colors found in hammerheads and wobbegongs.

When I discovered Sharks! (recommended by a Class Central user; thank you, Lisa) I knew I had to explore the course. I am so glad I did.

This excellent course, provided via edX, was created by Cornell University and the University of Queensland. The enthusiastic instructors William E. Bemis, Joshua Moyer, and Ian Tibbetts are ably supported by a raft of guest speakers. These specialists in various aspects of sharks such as brains, sensory organs, ecology and more are introduced through interviews, some in person and others (possibly especially produced for the 2020 session of the course) using video links. Teaching Assistant Ethan France was very active in the course discussions, with more than 200 well-considered answers to questions and comments.

As well as sharks, the closely related rays and chimaeras are studied, although the major focus is on the sharks. They are all part of the 1300-strong Chondrichthyan class. Did you know that ancestors of sharks had bony skeletons? The gene for bony skeletons is absent in Chondrichthyans, meaning that sharks have a cartilaginous skeleton.

Each week of the course explores a particular angle:

- Week 1: The Big Picture – Biodiversity and Evolution

- Week 2: Miracles of Evolution – Functional Morphology and Physiology

- Week 3: Thinking Like a Shark – Brains and Behavior

- Week 4: Sharks in the World – Human Interactions, Ecology, and Conservation

This has resulted in a well-rounded course that mentions just about any aspect of sharks that you can think of. Do you know why the Sand Tiger (Carcharias Taurus—known as the Grey Nurse in Australia) is considered endangered? As well as low numbers worldwide, another factor is that they are very slow to breed. Gestation takes 24 months, and, due to intra-uterine cannibalism, only two babies are born after that time, one from each uterus (yes, these sharks have two uteri). Compare this with the Spiny Dogfish (Squalus acanthias), which produces larger litters, allowing numbers to increase more rapidly.

Incidentally, Squalus acanthias is known by at least 160 different names around the world, in 38 languages. Because sharks are found in all the oceans, the importance of identifying them by their standard scientific names is obvious. We are shown a 1740 copy of Carl Linnaeus’s groundbreaking book, Systema Naturae, on naming organisms. A later edition of the book gave rise to the scientific naming system in use today.

Other engrossing links in the course include the tracking site, Ocearch, and the International shark attack file.

Amazing Facts

In this course, I learned some amazing facts about sharks. Did you know that as well as our five senses (sight, hearing, touch, taste, smell), sharks have two extra senses? Lateral line sense and electroreception both work particularly well in the marine environment. Lateral line sense can feel movements in the water from up to 10 meters away, while electroreception picks up electric fields caused by muscle contractions of nearby organisms. Apparently, both of these senses were found in prehistoric marine vertebrates, but after migration onto land, the senses became irrelevant and the associated anatomical structures were lost. One video describes experiments studying electroreception. When sharks had their electroreceptors temporarily deactivated, they had trouble locating and eating food, but were able to target prey again after the experiment finished.

Human interactions with sharks are explored in the final module of the course. These range from recreational and massive commercial fishing activities to aquariums and eco-tourism. The effects of overfishing in the North Atlantic Ocean and subsequent regeneration of the Spiny Dogfish (Squalus acanthias), after conservation measures were introduced is a positive story. Also mentioned is the 1972 Marine Mammal Protection Act, which led to higher seal numbers on California’s coast and a subsequent revival of shark populations in the area. As top-order predators, shark numbers often vary with the availability of their food source.

Shark Attacks

Interestingly, not all human encounters with sharks are “attacks”. Research has shown that many incidents are exploratory rather than aggressive. If a shark wanted to eat you, it wouldn’t bump you or leave teeth marks in your flesh, it would simply take a bite. The International Shark Attack File, administered by the Florida Museum, records non-fatal and fatal shark attacks worldwide. Reports of attacks go back centuries.

And how can you have a course about sharks without mentioning “Jaws”? This famous 1975 movie with a chilling soundtrack brought sharks to many people’s notice. The course links to an excerpt from the movie where the Great White shark (Carcharodon carcharias) is described by Hooper (played by Richard Dreyfuss):

“… we’re dealing with … an eating machine … all this machine does is swim,

and eat, and make little sharks, and that’s all.”

Sharks may be seen as eating machines by many people, but the course provides a much deeper understanding of their behavior, anatomy, and place in the ocean’s ecosystems.

Certificate

I enrolled for a free audit of the course, although it was tempting to pay. If I paid, I could have attempted the assessment items and earned a certificate, plus continued to access the course materials after the four-week free period was over. As I write, the course is currently archived. Although you cannot receive an edX certificate for the archived course, you can still access the excellent videos and other materials, including those fascinating links to other sites. And if edX releases another session in the future, the certificate will be available again.