MIT’s course review: World Music – Global Rhythms

Learn about musical rhythm from across the globe without reading music notation in this incredibly well-developed MOOC.

Course: World Music: Global Rhythms

Length: 5 weeks, 5-6 hrs/wk

School/platform: MIT/edX

Instructor: Leslie A. Tilley

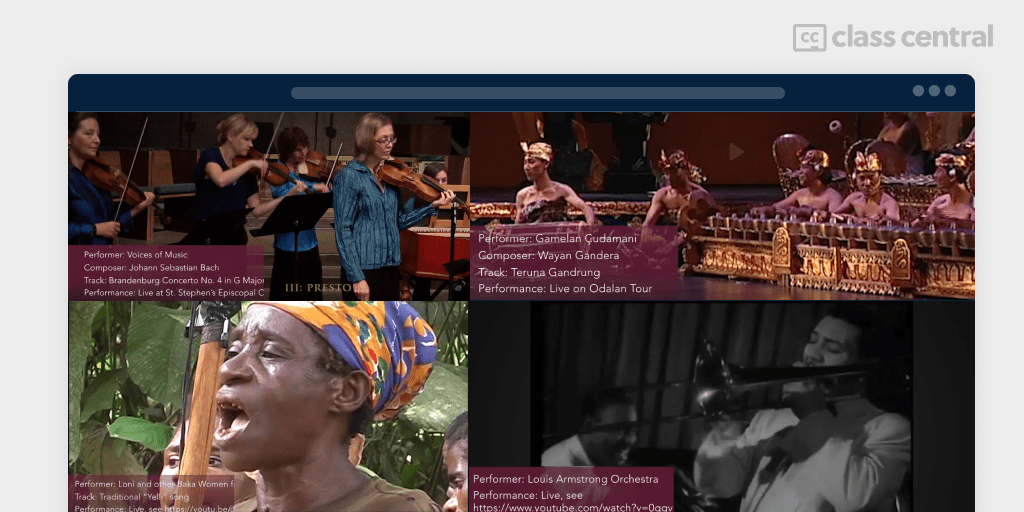

In this course, you’ll be learning about musical rhythm from across the world. You don’t have to read music notation to take this course; you don’t have to play an instrument. You don’t need to know any special musical terminology or theory to begin; You will learn all the concepts you need as we go… and the terminology and how it varies across the world. The course will explore music from all over the world and throughout time, from traditional African music, to Balinese Gamelan, to classical Japanese, Indian, and Western music, to contemporary reggaeton and punk music. You will learn how to recognize specific kinds of rhythms, and follow their development through time and around the world. You will also learn how different cultures developed different styles and ideas about rhythm, meter, melody and structure, and learn to start to distinguish some main ideas.

What Prof. Tilley does quite well here is encourage students to embody the rhythms she’s discussing, by embodying them herself. “Tap your foot!” she says, “shake your head, slap your thigh, clap, tap the table!” She has a good presence on camera without that deer-in-the-headlights stiffness so many MOOC professors get when they lecture. She’s constantly in motion – tapping, nodding, clapping, running a clip, demonstrating kriya – hand motions used in Indian classical music – conducting a beat with one hand, tapping the rhythm with the other. It’s a very engaging methodology.

For those with less musical background: True to the teaser, at no point is reading music required; everything uses felt/heard rhythm. If terms like “monophony” seem scary, don’t worry, they’re well explained.

About half the music discussed was familiar to me, present if not originally from the Western world: European classical traditions, American jazz, rock, and pop, ballroom dance from Austria to Cuba to Argentina. And to that point, Tilley doesn’t miss the opportunity to point out how rhythms from Western Africa ended up in twentieth and twenty-first century American top-forty tunes:

Now, you’ll find elements of the tresillo rhythm in a bunch of important timelines all over Africa and Latin America. And a lot of this has to do, unfortunately, with slave trading. Many really, really great drumming traditions in sub-Saharan Africa, out of which rhythms like tresillo grew, come from West Africa, places like Ghana and Senegal. And many of the people who were stolen from their homes and forced into slavery in North America also came from West Africa. And their rhythms traveled with them. So rhythms like tresillo are ubiquitous in pop music now. But they have a much longer history, which I encourage you to learn more about.

She also mentions Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s essay “The Danger of a Single Story” – an essay I’ve mentioned in these pages before – in connection with habanera rhythm:

The wonderful Nigerian writer, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, talks about what she calls the danger of the single story. When we know very little about a place or a people, the one thing we learn about them becomes a one-dimensional story of who they are. Not necessarily untrue, but definitely incomplete. And this is even more dangerous when there’s a power imbalance between the two sides as we inescapably get from a history of colonialism. The habanera rhythm in the 19th century became, in some ways, like a sonic, single story of Cuba and, by extension, the rest of Latin America and the Spanish-speaking world. And it became associated with characters like Carmen. And effective though that scene and that musical decision may be, she then becomes her own kind of single story and perpetuates stereotypes through that reduction. It’s a way to exoticize in a single sound. Lots to think about there and perhaps an online class isn’t quite the right forum to open up that particular Pandora’s box, but I hope you’ll listen to Chimamanda’s TED Talk and think about these important questions of representation in music and elsewhere.

In the I-Love-A-Good-Coincidence department: I usually have one old series going on Netflix at any given time as sleepy-time fare, and while I was taking this course, it was the comedy 30 Rock. Several times in the first season, I heard a habanera (S1E3,5:52; you don’t wanna know how long it took me to find that) – a different melody, but the rhythm was unmistakable.

Other topics included conducting motions for standard, cut, and three-four time; various kinds of multiple strands (monophony, biphony, homophony, and polyphony), syncopation, and density. Musical examples ranged from Asia to Africa and South America; although much of the music was Western, or at least Western-adopted, about half came from other places and showed the variety that might exist in, say, northern and southern India, eastern and western Africa.

The course consists of fourteen very short modules, each of which includes a couple of five-to-ten minute lecture/demonstrations, plus several activities: rhythm-matching applets (click the space bar on the beat; press p on the downbeat and q on the upbeat; etc), multiple-choice questions, discussion questions, self-graded essays. I took the audit course, so graded assessments were paywalled; for only $49 they can be unlocked. I found the rhythm matching exercises to be helpful, but difficult, since I can’t really tap my spacebar fast enough. And, perhaps the most important thing I learned from this course, it turns out I have a very poor sense of rhythm. Oh, I can handle four/four, three/four, six/eight times easily enough, but when it comes to other rhythms, I start to trip over myself. But it was fun to try.

I took this as a recreational MOOC, meaning I didn’t work very hard at it (one of the benefits of MOOCs is that you can choose where to focus your efforts; here, I let it be fun, not work). I think it would be a great course for anyone producing their own music, whether as an artist or for use in videos or games. Even for me, with no delusions of being a songwriter, the ideas were swarming around – “Hey, wouldn’t it be fun to use this and do that with it.” And it’s just interesting to see what music means in different places.

Music MOOCs are incredibly difficult to put together. I’ve taken several – including the Balinese Gamelan MOOC by the same MIT World Music faculty – and I can tell you, it’s not easy to convey elements of musical technique, theory, or style to unknown students of varying backgrounds in asynchronous format. Sometimes it works, like it did here, for the purposes outlined.

Republished from A Just Recompense (June 26th, 2022)