Capturing the Hype: Year of the MOOC Timeline Explained

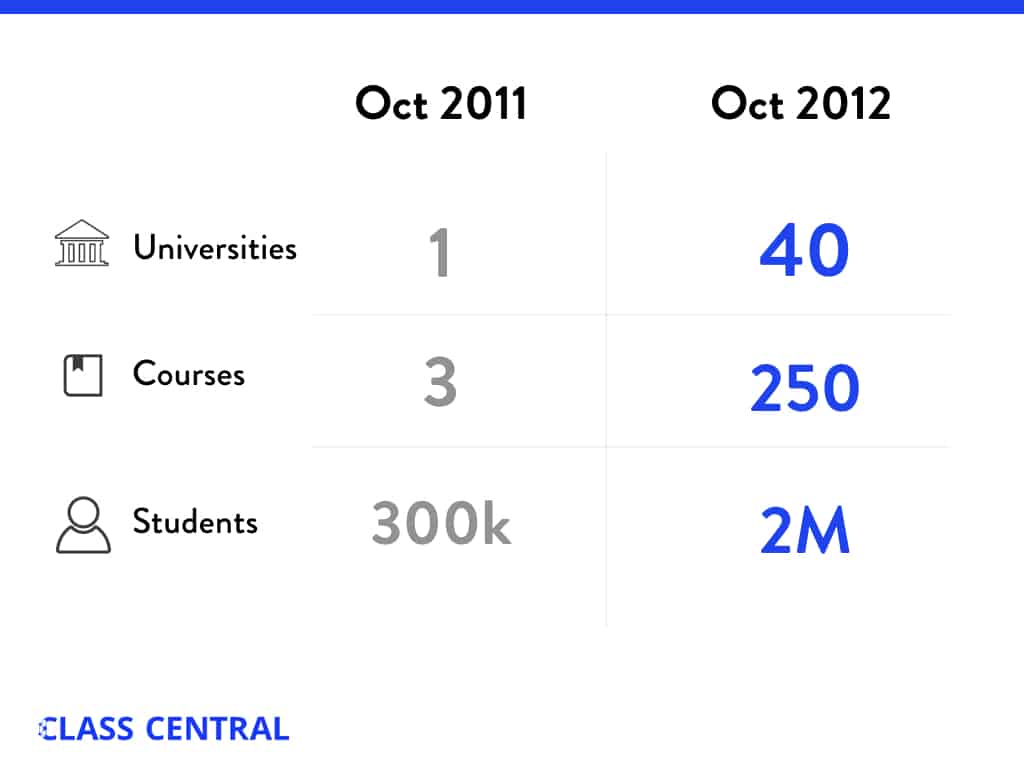

In October 2011, Stanford started offering three of their courses online for free. A year later, there were 250+ free online courses offered by 40+ universities. MOOCs were born.

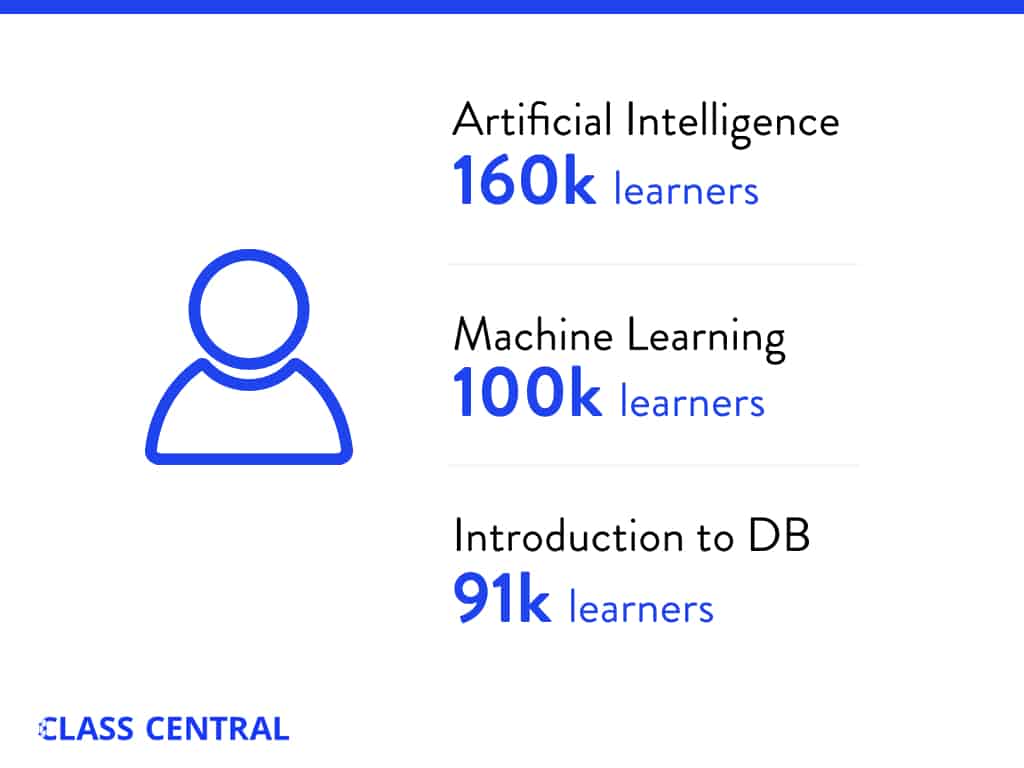

It’s been almost nine years since MOOCs went mainstream. I was one of the students who took the first of these courses, an Artificial Intelligence course from Stanford.

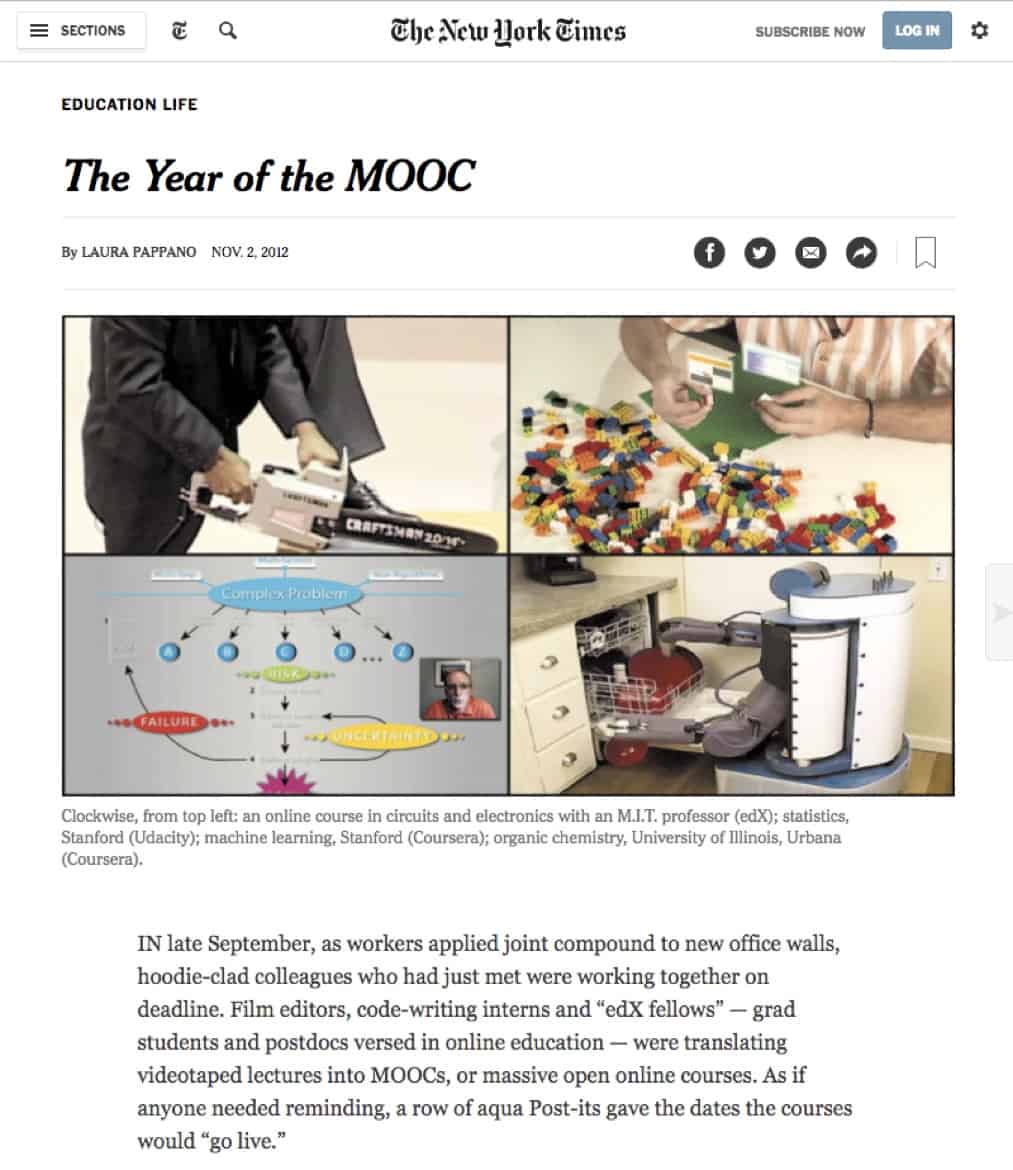

When I took the course, they weren’t called MOOCs, just Stanford online courses. Sometime during the first year, people started calling them MOOCs, for Massive Open Online Courses. It not only stuck but eventually led the New York Times to declare 2012 “The Year of the MOOC”.

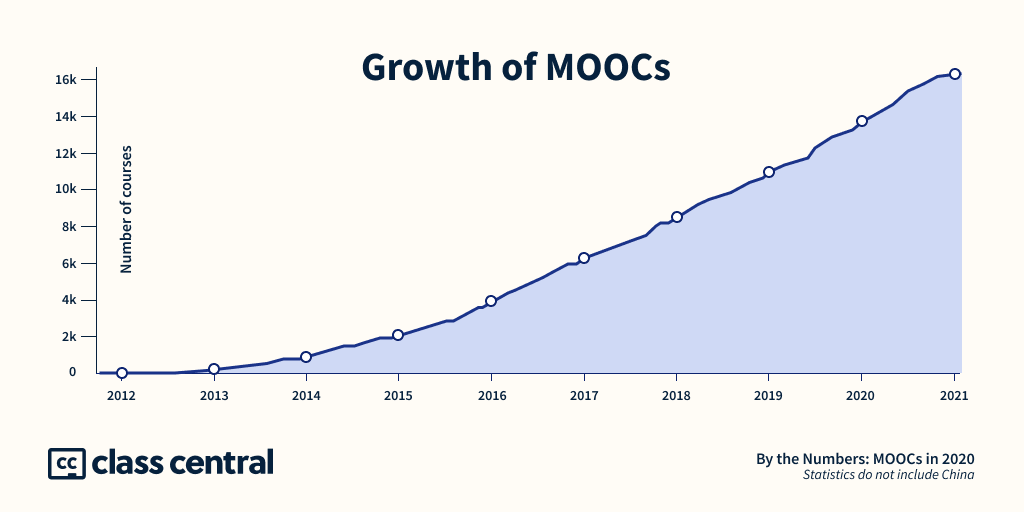

Last month, I wrote about how the hype surrounding MOOCs set things in motion and might have had a bigger impact than MOOCs themselves. In this article, I want to give you a sense of how this hype felt: a simple experiment that grew into a global phenomenon with 120 million learners, 13.5 thousand courses, 900+ universities, and 50 online degrees from providers all over the world.

Simply put, here’s the story of how Stanford’s online courses evolved into MOOCs.

(The article is based on a keynote on the evolution of MOOCs that I gave back in 2017 at a conference organized in Bangkok by the Thailand Cyber University.)

July 2011: Stanford’s Online Intro to AI is Announced

In July 2011, Sebastian Thrun announced through his personal Youtube channel that he and Peter Norvig would be offering a Stanford course — CS221 Introduction to AI — online for free at ai-class.org (which now redirects to Udacity, an edtech startup later founded by Thrun).

The course would be offered both to on-campus students at Stanford and to online learners around the globe. Online learners would be graded the same way as on-campus students.

Ten days later, Thrun released another video detailing how the course would work. This video also included Peter Norvig. Note that in the description of both videos, the word “MOOC” or “Udacity” never appears. We will come back to this later.

August 2011: Databases and Machine Learning Courses are Announced

A month later, Stanford professors announced two more online courses — one of them taught by Andrew Ng, who posted the announcement on his personal YouTube channel. Ng would go on to co-found Coursera.

Ng would teach a Machine Learning introduction at ml-class.org (which now redirects to Coursera), while Jennifer Widom would teach a Databases introduction at db-class.org (which now redirects to Lagunita, Stanford’s own MOOC platform).

Again, no mention of MOOCs or Coursera.

August 2011: 58,000 Learners Sign Up

Within a month of its announcement, simply through word of mouth, the AI class had managed to enroll 58,000 learners.

This led to the first of many articles about Stanford’s free online courses published by the New York Times, who I think played a key role in generating the hype around MOOCs.

October 2011: Stanford’s First Three Courses Go Live

On October 10th, 2011, Stanford’s three online courses went live, each with close to or well above 100 thousand students. I was one of those students, taking Introduction to AI.

October – November 2011: Stanford Announces More Courses

While the original three courses were in progress, more courses were announced by Stanford, each with its own website — for instance, hci-class.org (which now redirects to Coursera).

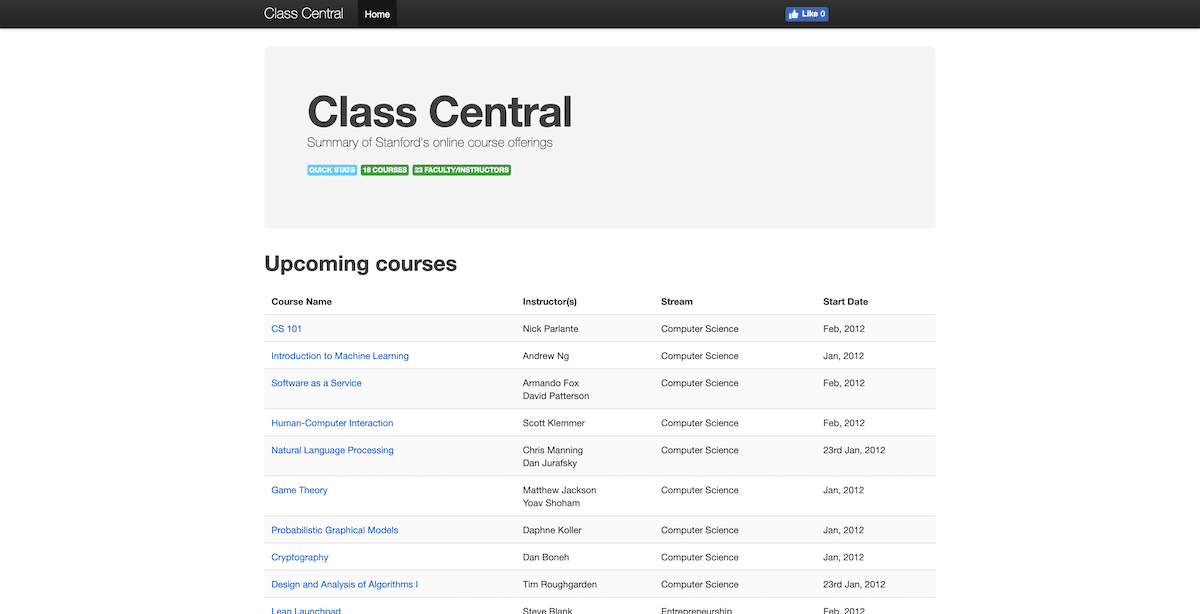

November 28th, 2011: Class Central is Launched

I was getting excited about Stanford’s online courses. So over Thanksgiving weekend 2011, I built a one-page website to keep track of them. Initially, all I wanted was to sort the courses according to their start date. Thus, Class Central was born, with a list of 16 online courses. The name was inspired by the “-class.org” used by Stanford for its courses.

December 19th, 2011: MITx is Announced

One month later, MIT announced MITx, an initiative to offer online courses through an open-source learning platform designed in-house. The initiative was led by Anant Agarwal, who would later become CEO of edX.

Once again, note that the word “MOOC” isn’t in the announcement.

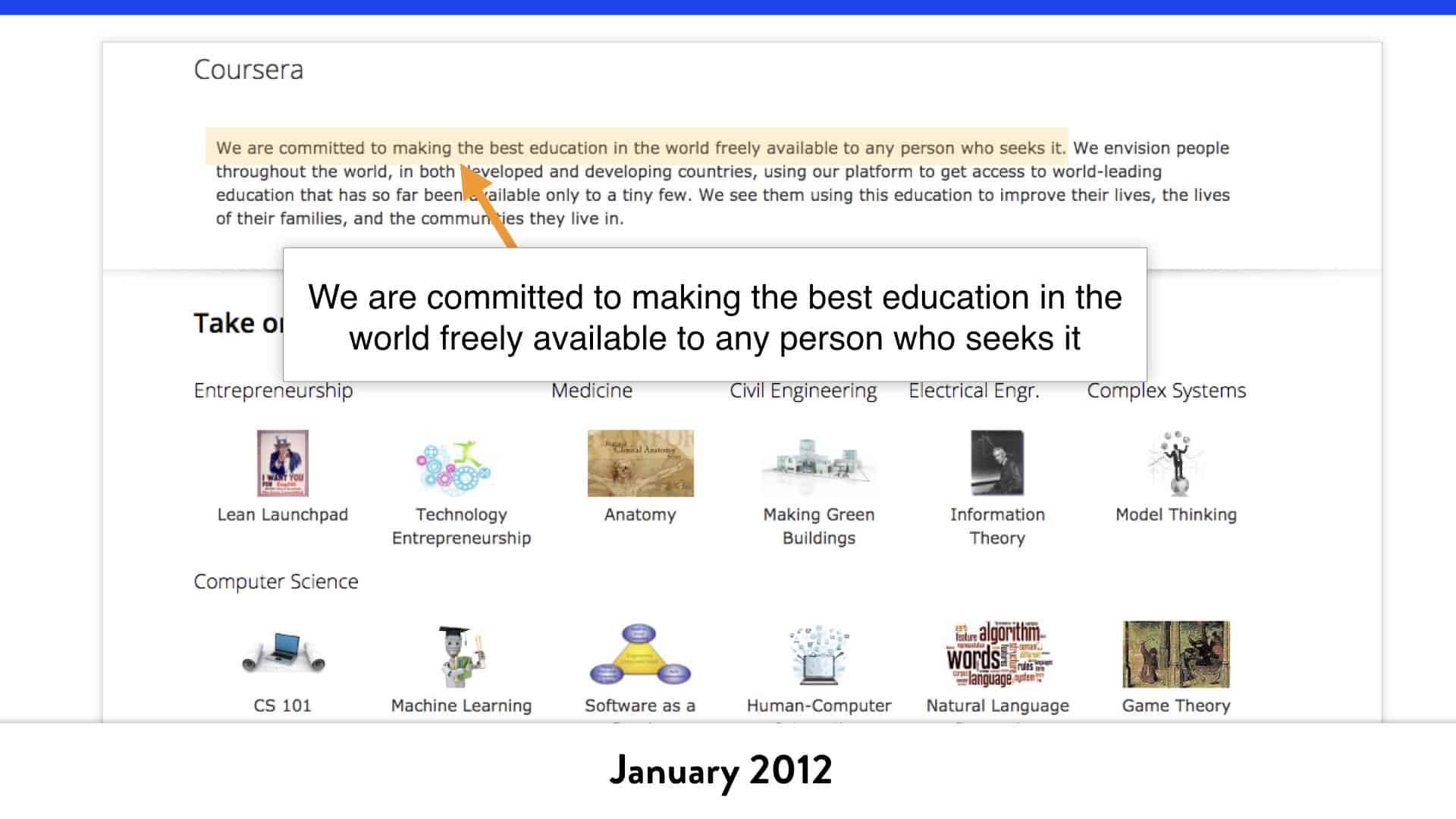

January 18th, 2012: Coursera Goes Live

On January 18th, 2012, Coursera’s website went live with the mission statement: “We are committed to making the best education in the world freely available to any person who seeks it.”

On January 18th, 2012, Coursera’s website went live with the mission statement: “We are committed to making the best education in the world freely available to any person who seeks it.”

At the time, Coursera had no business model, and it wasn’t clear whether it was a non-profit.

A few days later, Inside Higher Ed revealed that Coursera could be a for-profit company led by Stanford professors Daphne Koller and Andrew Ng. In the article, the word “MOOC” appears for the first time (as far as I can tell) to refer to Stanford’s online courses.

January 23rd, 2012: Udacity is Announced

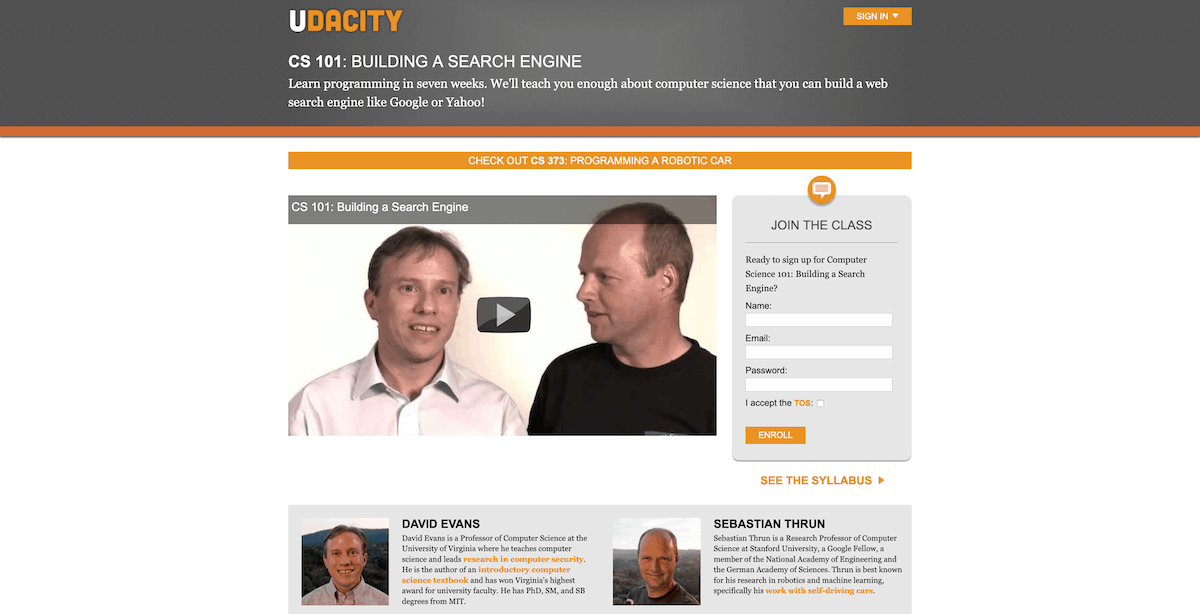

The team behind the AI class announced a new platform called Udacity and led by Sebastian Thrun. Udacity’s first two courses would be:

- CS 101: Building a Search Engine

- CS 373: Programming a Robotic Car

Unlike Coursera, which emphasized an academic approach, Udacity right from the start tried to be more project-driven (pivoting to career-driven a few years later).

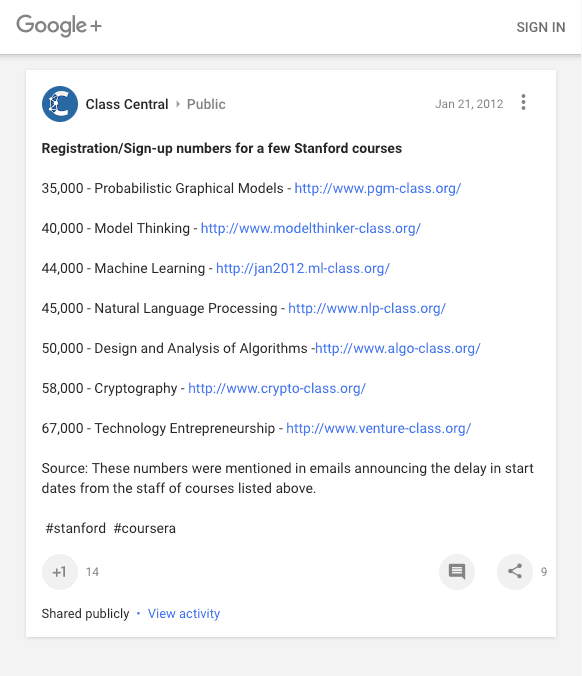

January 2012: Massive Enrollments

Stanford’s courses announced so far, which we by then knew would be hosted by Coursera, each got tens of thousands of enrollments. The courses were supposed to start in January, but start dates kept getting pushed back, presumably due to behind-the-scenes reasons related to Coursera being an independent, for-profit company.

February 20th, 2012: Udacity Goes Live

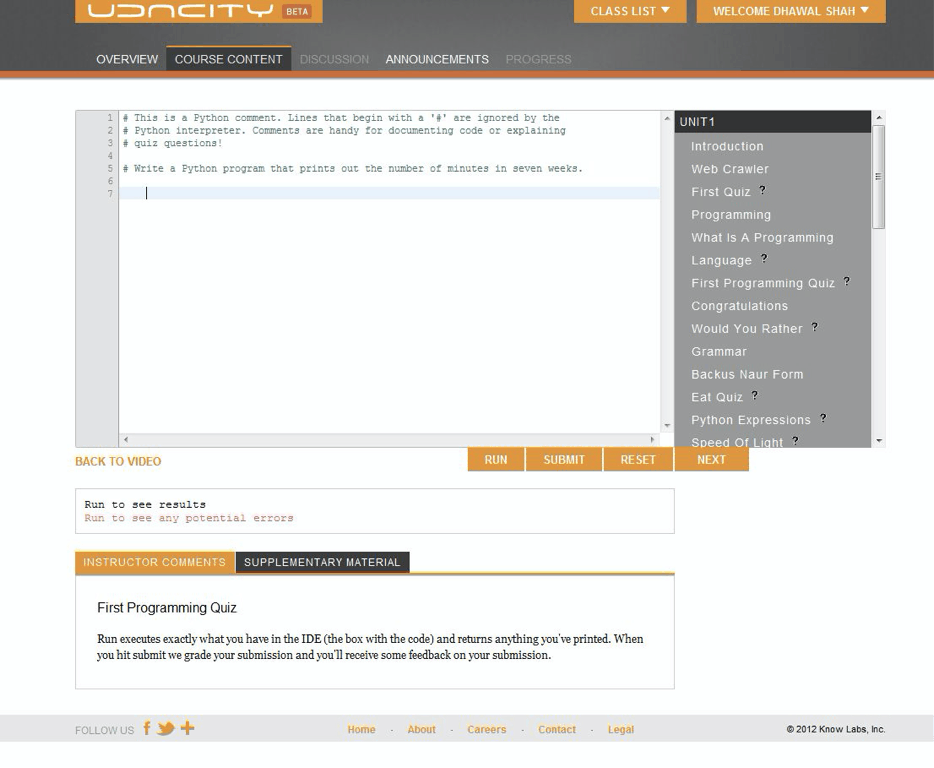

On February 20th, 2012, Udacity went live. The platform’s first course, CS101 Building a Search Engine, was taught by David Evans, Professor at the University of Virginia, and included a cameo from Sergey Brin, Google co-founder.

One of the platform’s interesting features was that the programming assignments could be completed inside the browser. Apparently, I was the first person to do a programming quiz on Udacity. At least, that’s what the email from the instructor said…

March 4th, 2012: MITx Goes Live

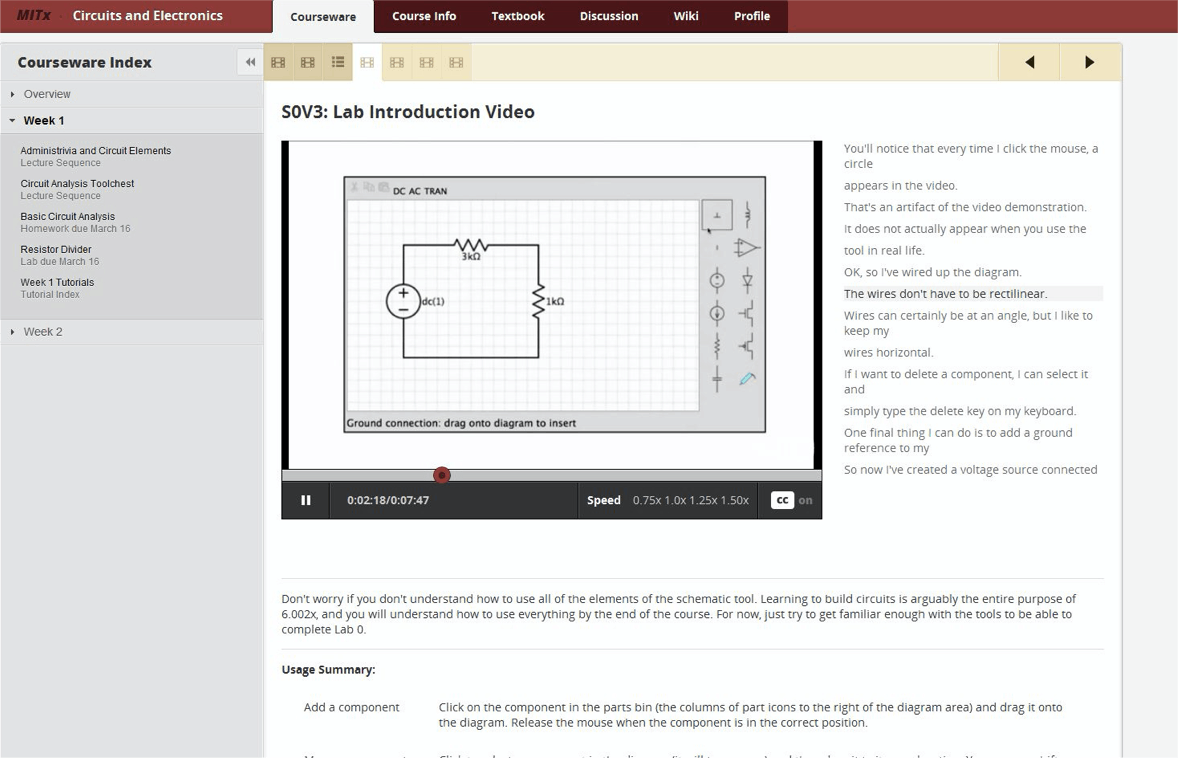

Two weeks later, MITx launched its first course, Circuits and Electronics, taught by MIT professor Anant Agarwal. The course had two interesting aspects:

- It featured an in-browser circuits laboratory that allowed learners to run simulations.

- It included access to Foundations of Analog and Digital Electronic Circuits, a seminal book on electronics co-authored by Agarwal. (Unfortunately, giving access to full books didn’t become a trend in online courses.)

April 18th, 2012: Coursera Raises $16 Million

A month later, Coursera announced that they had raised $16 million from Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers and New Enterprise Associates. They also announced new university partners: Princeton, the University of Michigan, and the University of Pennsylvania.

On April 23rd, Coursera’s first courses started. Coursera considers this period the birth of the platform and celebrates its anniversary each year in late April.

By then, the publications that wrote about Coursera’s funding round are still not using the word “MOOC.”

May 2nd, 2012: Harvard and MIT Announce edX

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SA6ELdIRkRU

On May 2nd, 2012, Harvard and MIT announced the creation of edX. Each university would invest $30 million to support the platform, which would be based on the software developed by the MITx team. A month later, the Gates Foundations announced a $1-million investment in edX.

Besides The Chronicle of Higher Education, no publication mentioned MOOCs while covering the edX announcement.

July – September 2012: Coursera Reaches 1 Million Learners, 33 University Partners, and 100+ Courses

In July, Coursera added 12 new university partners, including international universities, and the platform’s offering grew to over 100 courses.

In August, Coursera became the first MOOC platform to reach 1 million learners, with Udacity not far behind with 740 thousand learners. (Since then, Coursera has outdistanced other providers. You can find the latest numbers on Class Central’s 2019 analysis of the MOOC space.)

In September, Coursera announced 17 additional university partners, taking the total to 33.

By October, Coursera had well over a million learners and about 200 courses announced, of which 100 had already started.

October 25th, 2012: Udacity raises $15 million

In October, Udacity announced a $15-million funding round led by Andreessen Horowitz, taking the company’s total funding to $21.1 million. (There had been an unannounced previous round of $6.1 million.)

And that’s how the first year of MOOCs ended. We went from 1 university offering 3 courses to 300 thousand students to 40 universities offering 250+ courses to 4 million students.

Every month there was a new announcement, be it university partnerships, funding rounds, or milestones reached.

This led to FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) across higher education and Silicon Valley, which both invested huge amounts of capital and resources to launch free online courses without any concrete plan to recoup their costs or get a return on their investment.

Between announcements, think pieces were published and bold predictions were made by Sebastian Thrun envisioning the end of universities.

The media started calling this space “MOOCs” for Massive Open Online Courses, a term co-opted from a 2008 educational experiment. Eventually, the New York Times declared 2012 the Year of the MOOC — a term that just a few months before, most people had never heard.

BigDunc

What about MIT’s OpenCourseWare? I remember following some of their courses in the very early 2000s. Though I suppose it doesn’t really qualify as a MOOC, it was definitely a very early part of the history.

Monica

I really enjoyed this summary as I am one of the people who apparently lived under a rock and only encountered the concept and word of MOOC because of the pandemic. Somone posted about Coursera’s online offer of free courses on a social media feed, and during a late night fit of boredom I enrolled in a course without investigating much about it with the vague idea that I could use it towards my required ongoing professional development hours.

That course went well, I kept signing up for more, got my husband to sign up as well so we could do a course together and I wouldn’t have to seek assignment partners through the course discussion forums (one of the weaknesses of the MOOC formate, BTW).

I am now a full-on proponent of MOOCs and see myself continuously being involved in some course or another from now as as I LOVE the self-pacing aspect. Even so – I am only just venturing outside of Coursera to discover other MOOC providers, with your help. Though I respect that it all started with AI and IT and suchlike classes, I do wish there were was more depth of other types of areas also. I also discovered that I really don’t like the edX setup (much less intutitive than Coursera) and the single class I enrolled for there I promptly unenrolled from (A Spanish class which seems ancient compared to language apps I use, in the sense of how old the videos clearly are, and also how freaking much the instructors use English instead of the target language (as opposed to language apps where the spoken component is 100% target language from the start).

Anyway – this long post to say – well done you, for recognizing what was going on from the very first days, and for carving yourself a role out of the rocket phenomenon which helps others get a grasp on this whole new and at times confusing world.

And: my suggestion for future occasional blog posts would be for a round up of courses that focus less on mechanical/AI/natural science offerings, and more on psychology/sociology/language sorts of offerings.