What Taking a MOOC Was Like in 2012, During The Year of the MOOC

I describe the MOOC experience back when MOOCs were at their peak popularity.

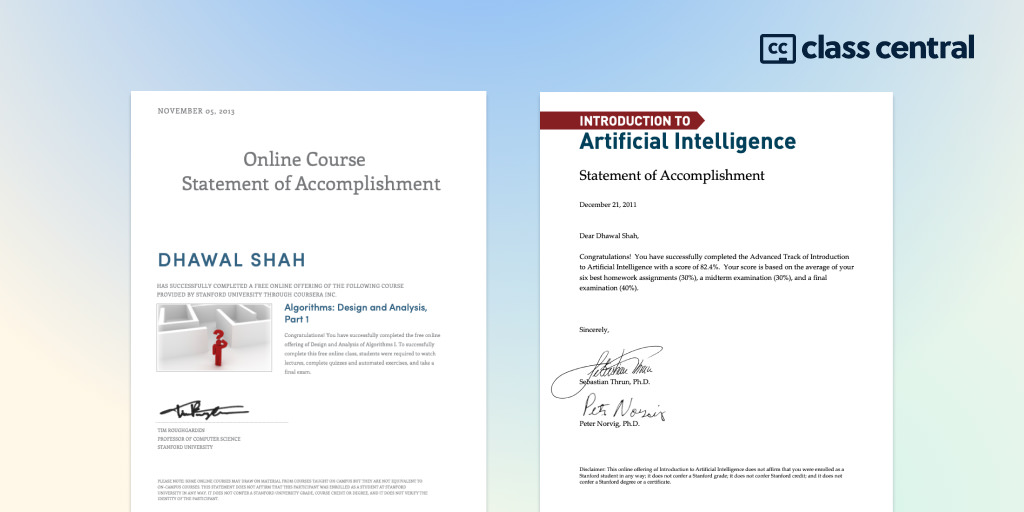

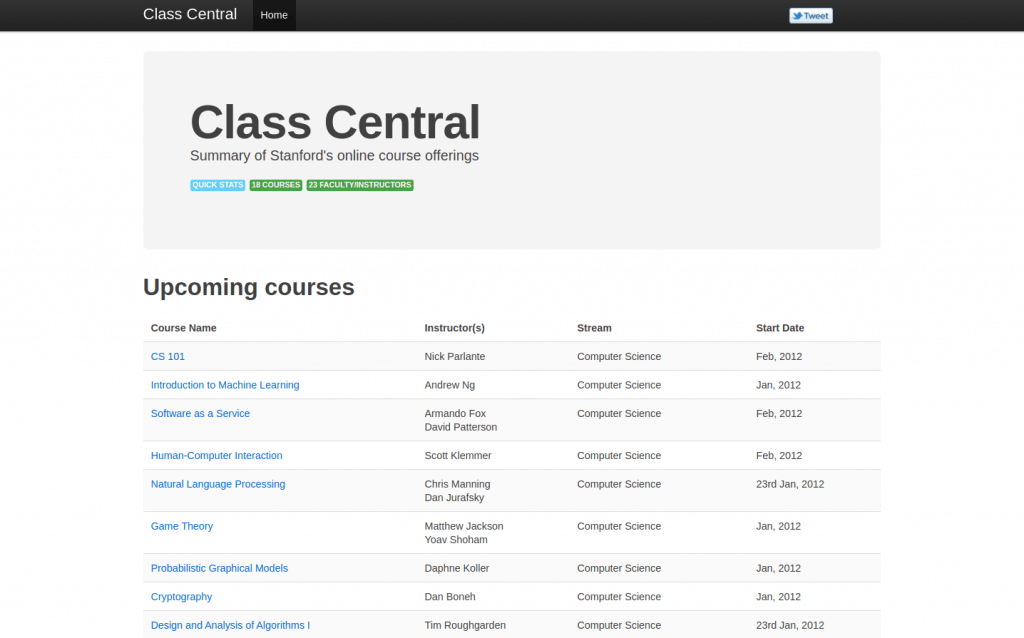

The first two MOOCs I completed had a significant impact on my life. The first one led to the creation of Class Central. And the second helped me find my first job in Silicon Valley, which would ultimately allow me to work on Class Central full time.

While I was taking these courses, I didn’t even know the word “MOOC“. Few did. Yet somehow, 2012 ended up becoming the Year of the MOOC. I tried to capture this MOOC frenzy through a timeline of the first year of the modern MOOC movement.

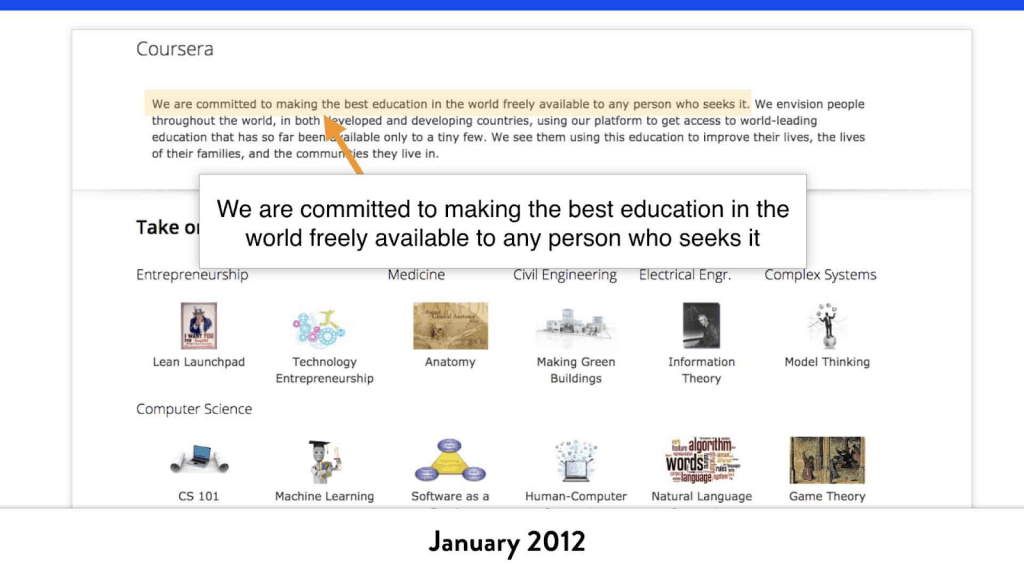

As I’m writing this, Coursera has just gone public and we’re approaching the 10-year mark since the 3 Stanford online courses that kick-started the MOOC movement went live in October 2011. The COVID-19 pandemic provided a big boost to online education and MOOCs in particular, which led me to call 2020 the Second Year of the MOOC.

Class Central records show that at the end of 2020, 950 universities had launched 16.3k MOOCs, 1180 microcredentials, and 67 MOOC-based degrees. The offering is significantly larger than it was in 2012, to say the least.

But as someone who’s completed many MOOCs since 2012, I can say that the experience has changed a lot over the years. Quality and breadth of content is objectively better now. But in my opinion, the overall course experience isn’t.

I thought now might be a good time to describe how taking a MOOC back in 2012 “felt” like.

Completely Free

Everything was free: certificates, videos, assignments, … In fact, there wasn’t a way for learners to pay even if they wanted to.

The first payment option arrived in January 2013, when Coursera introduced Signature Tracks. These were basically a way for students to verify their identity and tie it to their certificate. The certificates themselves were still free, but for an extra fee, these could be ID-verified. Eventually, they stopped offering free certificates altogether and put assignments behind a paywall.

Other providers took similar steps. Here are some articles I’ve written over the years, documenting these changes as they happened:

- Eyeing Revenue Sustainability: The Two Biggest MOOC Providers Adapt How Their Courses Work (2015)

- MOOC Trends in 2015: The Death of Free Certificates (2015)

- FutureLearn’s New Pricing Model Limits Access to Course Content After the Course Ends (2017)

- MOOCs Started Out Completely Free. Where Are They Now? (2017)

- EdX Puts Up A Paywall for Graded Assignments (2018)

- Coursera’s Monetization Journey: From 0 to $100+ Million in Revenue (2019)

“Real Courses”: Long, Challenging, Hard Deadlines, Exams

“What made it different was that this was a real course experience. It started on a given day, and then the students would watch videos on a weekly basis and do homework assignments. And these would be real homework assignments for a real grade, with a real deadline.”

– Daphne Koller, Coursera co-founder.

Early MOOCs were directly adapted from on-campus courses. In fact, Sebastian Thrun and Peter Norvig’s popular AI class was run simultaneously on campus at Stanford.

So they tended to be longer (up to 10–12 weeks) and more rigorous, with weekly or biweekly deadlines. As you can see above, activity peaked on weekends just before deadlines.

Assignments also had a limited number of attempts, which is currently still true for edX and FutureLearn.

Some courses even had a final exam, which was a plus, because I feel the current MOOCs rarely make me revisit old material, which is key for long-term retention. If I remember correctly, in Stanford’s AI Class, we had a 24-hour window during which we could start the exam. Once started, we had 2 hours to complete the exam, which consisted of multiple-choice questions.

MOOCs Were Actually Massive

The first MOOC I ever took had 160,000 learners enrolled.

The forums were buzzing with activity. New posts were added every few minutes. If I had a question, it had most likely already been asked and answered by someone else. At one point Coursera boasted about an average forum response time of 22 minutes.

I remember going to the forums just before the weekly deadlines and feeling that everybody was online at the same time, doing the same thing. It reminded me of my university days. But in this case, these were tens of thousands of learners across the world, sharing a global experience.

The shared experience, hard deadlines, and help from the community enabled me to finish courses that required significant effort — almost as much an actual university course.

There were in-depth discussions, not just a simple Q&A. Many learners went above and beyond to help each other, out of what felt like a true sense of community. I remember in one coding course, a learner shared test cases that we could use to test our code before submitting it.

While the pandemic brought more learners online, the upsurge in forum activity fell short of what it was in 2012. MOOCs’ massiveness is all but a thing of the past. To understand why, read MOOC Trends in 2016: MOOCs No Longer Massive.

Active Instructors & Real-Time Recording

Another particularity of the original MOOCs was that the instructors themselves were all early adopters. Many received little support from their universities and had to figure out on their own how to create MOOCs — for instance, how to record and edit video lessons.

Barbara Oakley’s Learning How To Learn is a good example of this. On a $5000 budget, she built a studio in her basement, taught herself Adobe Premiere Pro, and ended up creating one of the most popular online courses of all time.

Instructors also tended to be active in forums and actively listened to feedback. Often, while a week of the course was ongoing, instructors were recording the next week’s videos. So, later videos could be informed by feedback gathered in earlier weeks, giving learners some agency.

This gave the course a sense of interactivity. It helped it feel like a “real class.” By contrast, while production values have gone up, current MOOCs feel much more one-sided.

Driven by monetization, many providers shifted to an “on-demand” model with courses available throughout the year. As a result, instructors were largely removed from the equation. MOOCs evolved from virtual versions of classroom courses to experiences that feel more like a Netflix library of educational materials.

A few years ago, I proposed the concept of “MOOC Semester” to somewhat recreate the original characteristics of MOOCs: semi-synchronous, instructor-led, and sufficiently hyped.