Report Review of Siemen’s ‘Preparing for the Digital University’

Class Central summarizes the main findings from the MOOC Research Initiative (MRI) Report: Preparing for the Digital University.

In 2013, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation funded the MOOC Research Initiative (MRI) with an $835,000 grant to be administered by Athabasca University, to conduct further research on MOOCs. In addition to sponsoring primary research, the MRI produced a series of reports attempting to summarize findings from existing literature reviews. These reports were compiled into a 230-page collection published in February of 2013 entitled entitled ‘Preparing for the Digital University: A review of the history and current state of distance, blended and online learning’. It was authored by George Siemens (University of Texas at Arlington), Dragan Gasevic (University of Edinburgh), and Shane Dawson (University of South Australia). The purpose of the reports is to “introduce academics, administrators, and students to the rich history of technology in education…” (p. 7). It sounds like it has important things to say to a wide audience involved in MOOCs and online education. Are you intrigued but feel less than eager to dive into a 230-page report? Or do you want a handy summary of some of the main findings? That’s why Class Central has produced this summary…but the reports are quite readable, so if these findings are of interest, please do dive into the reports, and the numerous sources that they draw upon.

Format and Methods of the Report

The 230-page document was released under a Creative Commons 4.0 BY-SA license, and consists of six separate reports, each providing an overview of a topic area:

• ‘The History and State of Distance Education’ (Vitomir Kovanovic, Srecko Joksimovic, Oleksandra Skrypnyk, Dragan Gasevic, Shane Dawson, George Siemens)

• ‘The History and State of Blended Learning’ (Oleksandra Skrypnyk, Srecko Joksimovic, Vitomir Kovanovic, Shane Dawson, Dragan Gasevic, George Siemens)

• ‘The History and State of Online Learning’ (Srecko Joksimovic, Vitomir Kovanovic, Oleksandra Skrypnyk, Dragan Gasevic, Shane Dawson, George Siemens)

• ‘The History and State of Credentialing and Assessment’ (Charles Lang, George Siemens, Dragan Gasevic, Shane Dawson)

• ‘Where is Research on Massive Open Online Courses Headed?’ (Dragan Gasevic, Vitomir Kovanovic, Srecko Joksimovic, George Siemens)

• ‘Future Technology Infrastructures for Learning’ (George Siemens, Dragan Gasevic, Shane Dawson)

Each of these reports attempts to briefly summarize the topic, and point out the major conclusions from the research. As there is a large amount of research in these areas, the reports draw upon secondary or meta-studies (that is, studies of studies) to try to bring out consensus results–thus, the reports are tertiary studies. This allows them to be relatively brief, and though the conclusions are somewhat modest, the level of support for them is strong, being stable across numerous research contexts. We’ll note there has been some lively criticism of the report from Stephen Downes (and a somewhat surprisingly personal exchange between him and George Siemens (the two of them being the originators of the “first” MOOC).

A common methodology was followed to draw out the research for the first three reports on distance, online, and blended learning: a keyword search of peer reviewed papers, conference papers, doctoral dissertations and government reports, via several databases as well as Google Scholar, plus a manual review of 11 distance learning-related journals. 339 studies were found, of which 37 were drawn upon for the distance education report, 32 for the online learning report, and 20 for the blended learning report.

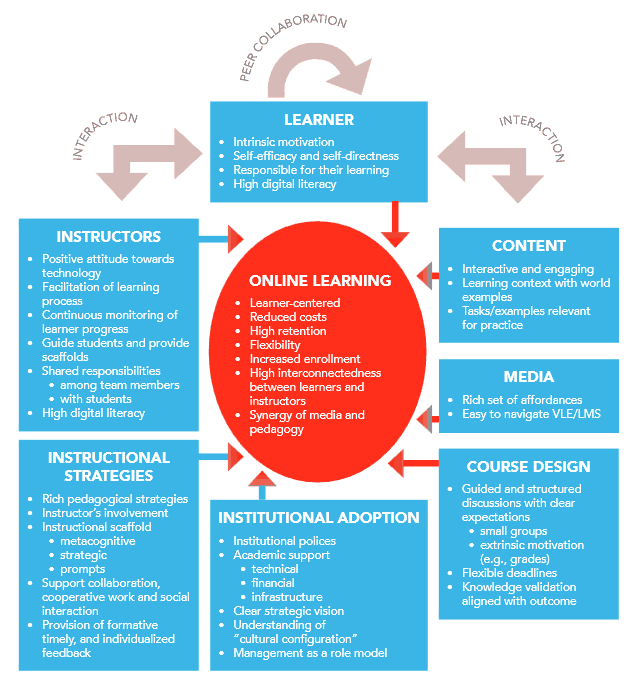

Below is a framework that was introduced to list the main influential factors in distance/online learning:

(Image source: Preparing for the Digital University, Siemens, G., Gasevic, D., Dawson, S., Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. p. 120).

Below, in each section, we’ll describe the methodology of the report and highlight some of the primary findings, as they appear to us.

Report Review: The History and State of Online Learning

For this report, 32 secondary or meta-studies were reviewed, each covering a dozen or several dozen primary studies in both higher education and adult learning contexts. Some of the primary findings are below:

• Online learning has been shown to be at least as effective as face-to-face learning, across multiple reviews of hundreds of independent studies

• The pedagogy used in online instruction has a large impact on learning, but the particular technology used has little impact

· However, visually engaging content is thought to be helpful

• A key pedagogical design element is to facilitate interaction, where student interact with course content, instructors, and peers. Interestingly, among these, student-student interaction and collaborative learning is most strongly associated with academic performance

· The most common channel for peer interaction was asynchronous discussion forums, and these were more beneficial when interaction within them was structured, moderated, and had clear guidelines

· Another important element is for students to have individualized feedback–much of this may come from the interaction described above. Despite efforts to provide some feedback via auto-graded quizzes, there is much room for improvement here, as the real value is in addressing the learner’s thought processes, and quiz explanations (when used) only partially address this.

· There were benefits to prompting students with self-reflection and self-assessment exercises

• From a student perspective, they tended to value “well-designed, frequently updated courses that incorporate extrinsic motivating factors, with tasks/examples immediately relevant to their practice, a reasonable level of control and flexibility (primarily in terms of deadlines), support to collaborate with their peers, and a high level of instructor involvement in providing summative and timely feedback” (p. 115)

• From an instructor perspective, to supply these beneficial pedagogical elements requires a greater amount of effort than designing a face-to-face classroom experience. A helpful trend here is that often small instructional teams are formed to produce and run online courses, however, support at the institutional level is often still lacking

· The biggest gaps are insufficient technical infrastructure and formally established policies and a shared vision for supporting online courses

Report Review: The History and State of Distance Education Report

Distance education has a long history and includes methods that pre-dated the modern internet (for example with mail correspondence or teleconference-based courses). Thus there is a greater amount of research here, and most of the 37 secondary studies were journal articles that covered dozens or hundreds of primary studies. Many of the findings are similar to the findings in the online learning report (re: effectiveness, pedagogical elements, success factors, etc.). Perhaps the fact that the results are so similar to the research on online learning (remember, per the methodology, these were separate studies) is additional support for the notion that the technological media through which we learn has much less of an impact than the pedagogy, and that the primary effect of the technology has been on accessibility. There were a few findings that were specific to distance education:

• Students showed slightly higher satisfaction with distance education vs. face-to-face education—distance learning students particularly valued the flexible pace and personalized elements of the learning environment

• Overall effectiveness of distance education (again, similar to online learning, was just as effective as face-to-face), has been increasing over time

• Among learner segments, effectiveness of distance learning was higher for professional learners than college students

• The use of learner-produced (i.e. user-generated) content was seen an increasing and promising trend

Report Review: The History and State of Blended Learning Report

Blended learning is used to describe the mixing of both face-to-face and online instructional elements, and is becoming increasingly common, especially in the K12 space (think of Khan Academy), but also in the higher education space with MOOCs. This report is based on a review of 20 meta-studies. There were surprisingly few conclusions that could be drawn, primarily because of the wide diversity of blended learning environments and heterogeneity in the way it was studied. Some conclusions were as follows:

• Results point to blended learning leading to superior learning outcomes compared to either 100% face-to-face or online learning; however, confidence in this conclusion is somewhat tempered due to the different definitions, measures, and approaches of the underlying studies that were drawn upon

• In terms of instructional practices, teacher-directed instruction and collaborative interactive learning were both superior to self-paced independent learning on objective learning outcomes. It is perhaps no surprise that this would be the case when measured against pre-established learning outcomes, but it was interesting to see collaborative learning do so well

• The major point the report makes is that most instructors approach blended learning as combining two separate components (online and face-to-face), without exploring the potential synergies of better connecting them together

· From a research standpoint, they note that most of the theory and design guidance comes from the online learning literature, and that unique opportunities brought about by blended learning have not been fully studied—thus, accounting for the dearth of conclusions in this report

Report Review: The History and State of Credentialing and Assessment

This short report (p.133-159) notes that credentialing is undergoing a shift both inside and outside the university. It presents a framework of looking at credentials across two dimensions: as having a fixed vs. flexible timeframe, and having assessment based on proficiency (i.e. knowledge) vs. competency (i.e. skill). Thus, the standard university credit-hour would be fixed-time, proficiency-based. The University of Phoenix would be an example of flexible-time, proficiency-based. The report points to the multi-course certification programs of MOOC providers, specifically Udacity’s Nanodegrees, as examples of fixed or flexible competency-based programs. It is unclear how helpful this framework is, but it may be a fine initial way to organize the different credentialing schemes that are emerging.

The report also mentions the use of badges, with its roots in gamification, and the useful open-source platform Mozilla Open Badges. It also mentions peer-based reputation credentials, such as those which accrue in platforms like Stack Overflow (you could add others, like reddit or Quora). The point is that there is the potential for drastically new options we’ll have available to define credentials…but of course the problem will be how to synthesize the right data into meaningful signals.

Report Review: Where is Research on Massive Open Online Courses Headed?

This report followed a unique approach to collecting sources. It consisted of analyzing the 266 papers submitted for the MOOC Research Initiative call for papers (only 28 grants were funded). These 266 papers, as well as the citations made within them, comprised the universe of sources that were then analyzed using network analysis techniques to determine key research themes. Below are some of the results:

• The main theme that cut across studies was that of engagement in MOOCs: how to measure it, how it relates to learners intentions, and understanding factors that affect it

• Another important theme was social learning—fitting as more than half of the authors were from the discipline of education, where there are deep theoretical roots on the role of social interaction on learning

• There should be an increased research focus on enabling skills among learners is important, as much of online learning requires learners to be self-regulated: metacognitive skills, learning strategies, and attitudes

• Given the worldwide spread of MOOCs, there should also be greater geographic diversity of researchers and studies, as most studies are currently drawn from a North American setting

Report Review: Future Technology Infrastructures for Learning

This report is an overview of learning technologies. It also describes four generations of technology development in the following way:

Generation 1 : basic echnology use, e.g. computer-based training

Generation 2: learning management (LMS) and content management (CMS) systems

Generation 3: diverse, fragmented systems, e.g social media, e-portfolios, MOOC providers, etc.

Generation 4: distributed technologies, adaptive learning, distributed infrastructures, and competency models

The report notes that we are currently in the midst of developing Generation 4 systems. The report goes on to evaluate several different technologies, and analyzes them along a spectrum of focus from the individual to a larger collective, across four characteristics: control, ownership, integration, and structure. As with the credentialing framework described earlier, it is unclear how this framework can be helpful, but perhaps some will find it a useful tool.

Overall Comments

A few final thoughts on this 230-page report. The main takeaway that we think is important is for people to understand and be exposed to the history of research that has been done on online learning, that it has roots in distance education, and that there is enough research that studies or studies, and studies of studies of studies have been done (as well as this summary of studies of studies of studies). Online education is not new and we know more than most realize. Some of the conclusions may be obvious to some involved in online learning projects: that online learning can be as good as (or better) than face-to-face learning, that interaction is an important element in learning. Some may be a surprise, such as the fact that the particular technology used has relatively little impact on learning outcomes, while pedagogical approaches have large ones. This can be a healthy check on the tendency to blindly follow technology-solutionism (from a practitioner perspective, see Why My MOOC is Not Based on Video).

On the “room for improvement” side of the ledger, while these reports collect a nice set of meta-studies, it would have been nice to have walked through some of the key ones in more depth, or provided a summary of each, as a guide to the reader on where to dive in further. The reports beyond the distance/blended/online education ones were fairly lightweight, with few significant conclusions. Also, the nature of tertiary studies means that though conclusions may be strong, they tend to be fairly general because they are drawn from so many different research contexts–the trade-off for high confidence in a survey of a body of work is decreased specificity. Still, it is good to capture and synthesize the well-known findings. Let’s not forget that innovation and experimentation in something as important as education should be done with awareness of the rich research and diversity of actual practices that that exist.